With a friend from a computer club, he created one of the first Slovak games to be sold in the early 1990s. Quadrax was inspired by Tetris, but it has come a long way since then, and is now considered a gaming classic among fans.

A few years later, Marián Ferko and Dávid Durčák founded the company Cauldron, which was the first in Czechoslovakia to professionally create computer games.

For over twenty-five years, they have collaborated on several strong titles with the major publisher Activision and under the Czech brand Bohemia Interactive.

Today, their studio is called Nine Rocks Games and specializes in hunting games. Its sales last year increased from 1.7 to 2.5 million euros. In terms of economic performance, it ranks seventh in the Slovak gaming industry. Of the studios that create computer and console games in our country, none has a higher turnover. The leader of the entire Slovak gaming business is Pixel Federation, which has sales of almost 51 million thanks to the creation of mobile games.

The company is currently completing its first title for its owner, Austrian publisher THQ Nordic. The game is aimed at adult gamers and will attempt to get as close to the reality of hunting as possible with realistic physics and gameplay.

Marián Ferko is one of the studio's team leaders. He is also the president of the Slovak Game Developers Association (SGDA) and teaches at the Academy of Performing Arts in the Game Design department, which he helped found.

In the interview you will read:

- what the beginnings of game development in Slovakia looked like,

- why the original Cauldron studio gradually became under the brand Bohemia Interactive and finally THQ Nordic,

- why the domestic gaming industry is still twenty years behind the West.

You developed your first commercial game when you were about eighteen. How did your parents feel about you wanting to get into games at the time? Did you know then that you wanted to continue doing it for the rest of your life?

When a person is creative, and I have always drawn and created a lot in the past, it is completely natural that they try this or that for a while. Parents will always support their children, no matter what they do. When you draw comics, for example, you can reach a certain level, but you will not discover anything new there. Digital creation is interesting in that you can create things there that cannot be created anywhere else. Neither creations on canvas nor sculptures reached the level that could be created in the digital space, plus the works are also interactive, unlike paintings, for example. In the format of the digital space, the possibilities of creation have constantly shifted. This means that a person can create and discover something new all their life.

How did you actually get into computer creation before the Gentle Revolution?

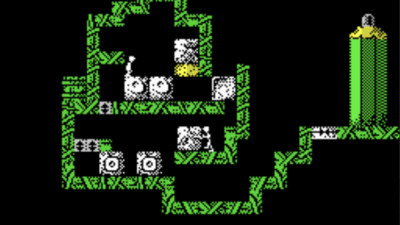

When I first encountered 8-bit computers in the 1980s, like the ZX Spectrum, they couldn't be imported into the former Czechoslovakia at that time, still under communism, because we had the Iron Curtain. I was lucky that my brother's friend's father worked on a ship, had the opportunity to travel to Austria and smuggled some computers.

Back then, it was smuggled in chocolate boxes, a person would buy a chocolate box, take out the contents and put a computer in there, repackage it and could take it across the border. Or people would hollow out the inside of a loaf of bread and put a computer in it. So the necessary technology came here slowly and gradually, and whoever had it was very lucky.

In elementary school, I came across computers like the ZX Spectrum and later the Didaktik Gama, which was produced by the company Didaktik Skalica. This company initially mainly produced teaching aids for physics. However, as a state-owned enterprise, they were given the task of producing a computer, even though they had no experience with it. They developed an absolutely brilliant computer that made a breakthrough in the IT industry here. Many leading specialists grew up on an 8-bit basis.

Computer clubs were also important in the 1980s, where the IT community of the time was concentrated. How did they work?

They were under the thumb of the Union for Cooperation with the Army, which paid for the premises where we had televisions and we brought our own computers. At that time, children already had Didaktiky, which cost six thousand crowns, while the salary was fifteen hundred, so they were really expensive machines. There, children made games and applications, and when someone made their own game, they presented it in the club and we knew about it then. That's how I met Dávid Durčák, who, as the director of Nine Rocks Games, sits a few offices away. He is a programmer who has more experience in the technical implementation of the work, I am more oriented towards the graphics side.

And with him you also developed the computer game Quadrax.

With him, we made Quadrax for the 8-bit platform and the game was released on cassette tape.

That was in 1993. Did you manage to sell the game then?

At that time, the company Ultrasoft was being formed, which was engaged in the sale of computer equipment and software from several creators in Slovakia. We did not make the game with a commercial goal, but when we had it and it looked really good, we tried to sell it to Ultrasoft. We signed a contract and waited another year for the game to be released, because Ultrasoft waited until it had collected a sufficient amount of software, and only then did it multiply and sell it.

So the game was only released in 1994, quite late, when 8-bit computers were already giving way to personal computers.

What did game distribution look like in the early days of the game market in our country?

Before Ultrasoft, there were no distribution companies in our country, even though there were already many computers in Czechoslovakia. However, the games that were smuggled here had to get from Pilsen to Košice. People spread the applications among themselves through personal contacts and gradually got them from one end of the republic to the other. This is how communication channels existed here. However, the games could only be spread by copying them illegally.

When someone wanted to do business with games, it was difficult because everyone was used to the idea that they were not bought, but only copied. So first the company had to convince people that copying was theft. Or to be able to protect the product against copying. We have a very clever software developer here who made such copy protection on the Quadrax. It was very difficult to remove and in fact it was only possible to order a tape from that dealer, because the tape could not be digitally copied.

So then you sold it like this through Ultrasoft.

Yes.

A few years later – in 1997 – you founded your own studio, Cauldron.

When we finished Quadrax, we wanted to try something different, so we started making a game, not for an 8-bit computer, but for the PC. We decided to make something that we already knew, and we based it on the Quadrax system, because the system was original and there were no games like it. So we made a version of Quadrax for the PC, and in the process we got the opportunity to start a company.

Did you start the company with the capital you had from the sale of the original game?

We made about enough money from the initial sales to buy a soda at a restaurant. We only sold a few cassette tapes because the platform was on the decline. If we had released the game a year earlier, when we invented it, it would have been different.

So we didn't have any capital, but we had contacts and we also went to clubs. Then a friend came up with the idea that he had an acquaintance who was already running a business, had some capital and wanted to invest it. So Peter Rjapoš was our "angel" investor. We met and founded the company Cauldron, which had the goal of professionally producing games in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. This is how the first company in the Czechoslovak space was created that was founded solely to create games. Few people believed it at the time.

You then developed quite successful games like Spellcross and Chaser. What was it like publishing once you had your own company?

It was very exciting. When we founded Cauldron, we knew that we had to aim for global markets. And the problem was that when you start a bakery, for example, you have income from the first day you bake rolls, because you sell them right away. But with us, it's a little different, because we bake the game for quite a long time, about a year and a half, and only then do we start selling it. So we had to have capital to cover a long period. There were three of us working there, and eventually four, and Dávid Durčák, I, and the screenwriter didn't receive any salary. Our parents supported us. All we paid for was the premises, lighting, electricity, and the purchase of computers and software. That was the whole investment.

We knew that when the product came out, it had to be successful, because if we baked the product poorly, we would be out of business very quickly. We wouldn't have any more capital. So we planned our one shot well. We did extensive research on what games were selling, what games were successful, and there was careful planning that we followed. We came up with Spellcross, which was a military strategy game with a theme of modern military technology and magic, which was a combination that had never been used before.

You operated under the Cauldron label from 1996 to 2014. You made quite a few titles in the meantime. What was your business model?

We then worked with various companies and finally with the large publishing house Activision, for whom we made many titles for the North American market. Activision gave us licenses and guidelines for the game to operate in order to be successful in the market. We made a game for them, which they then placed on the market. The hunting games we worked on were some of the most valuable titles they had.

After eighteen years, Cauldron has been rebranded by Czech publisher Bohemia Interactive. Why?

We have been working with Activision for a long time, but in 2014, a global problem arose that affected all game developers, and that was the switching of game platforms. Previously, whenever the Playstation platform ended, the Xbox platform remained at the same time, and vice versa, when the Xbox platform changed, the Playstation platform was stable. Then there was a period when both platforms changed architecture and hardware at the same time, and it was not clear how many titles would be sold on the new PS4 and Xbox One platforms that were coming, and how many would be sold on the old PS3 and Xbox 360. So none of the investors wanted to invest in new titles because they didn't know how they would sell, so they preferred to wait. We had signed contracts with Activision for other titles, but these contracts fell through.

So we had a plan B, but it was such a bad time that no one wanted to start a new title with us. The only option left was to quickly take advantage of Bohemia Interactive's offer. They worked in a slightly different way at the time. They developed the title DayZ, which unexpectedly became very successful, and they knew they needed to develop it. But they were not equipped for that and needed a team that would adapt the game to the Playstation and Xbox gaming platforms. We had extensive experience with that, so our cooperation was logical. So Bohemia Interactive was founded in Slovakia and the entire Cauldron team was employed there.

You worked with them until roughly 2020. Why did your collaboration end?

Up until then, we were used to making one game a year for Activision, sometimes even two top-quality titles a year. The work pace was crazy, if we didn't work until five on Sunday nights, Activision would be nervous that they weren't getting new data. But with DayZ it was different and we worked on the project the whole time.

Together with the teams in Prague and Brno, we changed the technology under the hood, so the game had to work on the servers, but we had to change everything there. We specialized in certain technologies that we had experience with. You have to imagine it as if you had to change all the parts of an airplane during the flight, from the wings to the seats to the engines, without the plane having to land. People here started to get tired of it. After a while, key people in Bohemia resigned, and that was the impetus for the founding of Nine Rocks Games. However, I can't say a single bad word about Bohemia, they helped the Slovak gaming industry a lot.

We founded a new company, advertised new job positions, and everyone from Bratislava's Bohemia applied for them.

You founded the new studio under the umbrella of the Austrian publisher THQ Nordic, which belongs to the Swedish Embracer group. How did you get involved with them?

We already knew the people from THQ Nordic, we worked with a company that is currently also part of THQ Nordic on the title Chaser. In our business, if you put on Linked-in that you are free, and important people notice it, they will ask you if you are looking for a job with them. At that time, THQ Nordic was looking for where to invest, buying out existing teams and starting new companies. We were ideal for them because we had the experience, the drive and the key people were unemployed.

What kind of autonomy do you have under this publishing house and how does the Austrian company finance you?

We decided to continue developing hunting games because we had many years of experience as a team, we knew what we wanted to do, we had a dream game that could be realized. We did market research and we knew that there were quite a lot of customers and relatively few titles, so it seemed like the least risk to us. We have some milestones by which we have to fulfill specific tasks, and these have to be approved by THQ Nordic. We receive money for development every month and everything is controlled by the publisher. But the design of the game, as well as the story, was up to us. That is the advantage that we can choose what we want to do. However, it is not our company, so one day the decision may come that we will stop or that the game is not selling, and we have to work on something else. But that will not happen. We know that the title we have is the best on the market and will be successful.

What level is the gaming industry in our country compared to neighboring countries?

Communism has done terrible damage here, which is reflected in everything, and it is also the case in the gaming industry. We are still twenty years behind the West. It is because there was no access to computers here and the people who are currently in management positions do not understand games. I see a great demonization of computer games here. It is something that is considered very bad. In the West, people who grew up with games as children are now in key management positions. If you look at the support programs and subsidies that are available abroad, they are on a completely different level.

Until things change here, the generation has to change, otherwise it won't work. I went to a school in Belgium that focuses primarily on game design, where they accept 1,300 students for the first year. At our Academy of Fine Arts, we barely accept eight. And it's always about people. If you don't have them, you can't build a strong enough industry. One thing is that people have to be educated, and the other thing is that they have to stay in Slovakia. Currently, the most talented people are leaving to study abroad and only a few are coming back. We have a big outflow here, which we don't need to stop, but to make our environment attractive enough for them to come back. And this is connected to everything, with the judiciary, politics, healthcare, and unless this changes, all other forms of business will suffer, not just the gaming industry.

The Czech Republic and Poland were also communist, and Poland is quite prominent in the gaming industry.

The answer is in their number. The problem is that you need a very specific person to create games. Not just any person can do that, it is technically very demanding. If it is connected with artistic expression, then you have to have artistic feeling and technical thinking. There are extremely few such people on the market. Poland has the advantage that there are many of them, and so there are statistically more talented people. The greater the probability that they can meet there. The same applies to the Czech Republic.

The biggest profits in the gaming industry in Slovakia and around the world are made by studios that create games for mobile. Have you ever thought about switching to this platform?

Yes. In addition to Cauldron, we also founded the company Top3Line, where we tried to make mobile games. But if you want to be successful at that, you have to really focus on it and not do anything else. We simply didn't have the time, and the mobile games we created weren't that successful.

So the process is that different from developing games on PC and consoles?

It's more fun to make games for consoles and PC. Mobile games make a lot of money, they're very successful, but they're not attractive enough for us. It's not a challenge for us.

You lecture at VŠMU, how did you get into it?

When I was hiring people at Cauldron, when we needed to expand and I hired someone, no one had any experience with game development. We had to train each employee for quite a long time. So I asked myself why schools and the state couldn't do this for us. When several game companies were being established in Slovakia, everyone had a problem with qualified people and every studio was also an educational center. The solution is that experienced people from the industry have to go to school and educate the new generation. So when we founded SGDA, miracles started happening and, among other things, we established cooperation with several universities in Slovakia, which already include game creation in their programs.

What was the significance of founding the association?

The association already acted as an authority, so we started communicating with the Ministry of Culture. And we started to work closely with the Art Support Fund, where we developed a program to support the development of computer games, which is now bearing a lot of fruit. And the education in the field of computer games at the Academy of Performing Arts will certainly bear fruit. Behind it is Professor Ľudovít Labík, who has been creating an education program in visual effects for years. With him, we also founded a game design study and we already have students who are going into the third year of bachelor's studies. I also lecture there on interactive visual effects.